The Abstract Factory design pattern is a creational pattern that handles object instantiations. It offers a framework to manage complex object creation scenarios and helps us achieve a more maintainable code structure.

In this article, we’ll look into the Abstract Factory design pattern and how it helps us achieve modular and loosely coupled code.

Let’s begin.

What Is the Abstract Factory Design Pattern?

The Abstract Factory design pattern enables clients to use an abstract interface to generate a family of related products without knowing about the concrete products this interface produces. This is one of the core creational design patterns.

By encapsulating this creation of related objects, we decouple the client code from the actual implementations of the objects.

Abstract Factory Components

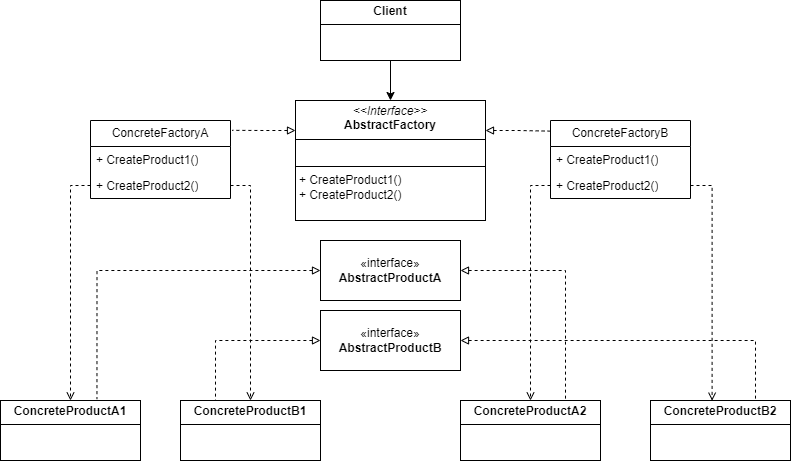

This design pattern involves several key components:

The Abstract Factory is an interface that declares a set of abstract creation methods. It does not specify details about concrete products but rather focuses on structure. A Concrete Factory is an implementation of the Abstract Factory interface, which we use to create concrete product objects.

The Abstract Product is an interface that defines the structure that the concrete product should have. In turn, a Concrete Product represents an implementation of the Abstract Product.

Finally, the Client is the class that uses the Abstract Factory and Abstract Product interfaces. However, it is decoupled from any specific variant of client products it gets from the factory.

Why We Need the Abstract Factory Pattern

Let’s consider a scenario where we want to implement a theme park. The theme park has different sections – for instance, Adventure and Fantasy. Each section has its own type of ride and show.

Let’s try to implement this without using the Abstract Factory pattern. First, let’s create the AdventureRide class:

public class AdventureRide

{

public void Start()

{

Console.WriteLine("Starting the Adventure Ride.");

}

}

Then let’s create the AdventureShow class:

public class AdventureShow

{

public void Begin()

{

Console.WriteLine("Beginning the Adventure Show.");

}

}

Thus, with these classes created, we have the “Adventure” section of the theme park complete. Similarly, we can create the FantasyRide class:

public class FantasyRide

{

public void Start()

{

Console.WriteLine("Starting the Fantasy Ride.");

}

}

As well as the FantasyShow class:

public class FantasyShow

{

public void Begin()

{

Console.WriteLine("Beginning the Fantasy Show.");

}

}

Finally, let’s assemble these parts to complete our theme park by creating a ThemeParkClient class:

public class ThemeParkClient

{

public void EnjoyThemePark(string section)

{

if (section == "Adventure")

{

var ride = new AdventureRide();

var show = new AdventureShow();

ride.Start();

show.Begin();

}

else if (section == "Fantasy")

{

var ride = new FantasyRide();

var show = new FantasyShow();

ride.Start();

show.Begin();

}

}

}

Here, the EnjoyThemePark() method calls the appropriate ride and show methods depending on the section of the theme park. With this, we have completed our theme park.

However, while this setup works fine for our current requirement, we start seeing problems as soon as there is talk of park expansion.

Problems When Not Using the Abstract Factory Pattern

Our code violates the open/closed principle. Let’s assume we want to add a new “Sci-Fi” section to our theme park. We’ll need to modify the ThemeParkClient class to handle the new rides and shows, but the open/closed principle states that we should only be extending the class, not modifying it.

In addition, our code is not scalable. As the number of sections grows, the ThemeParkClient class grows in complexity and becomes difficult to maintain.

Finally, the ThemeParkClient class is tightly coupled to the concrete ride and show classes, e.g. FantasyRide and AdventureShow. This makes it difficult for us to update these classes without modifying the client code.

Transition to the Abstract Factory Pattern

To address these issues, let’s decouple our client from the concrete implementations by using the Abstract Factory pattern.

We’ll start by creating abstract products, one of the core components of this design pattern. Let’s start by creating an IRide interface:

public interface IRide

{

void Start();

}

Next, let’s create the IShow interface:

public interface IShow

{

void Begin();

}

Now, all our concrete products will implement these interfaces. The AdventureRide and FantasyRide classes implement the IRide interface:

public class AdventureRide : IRide

And the AdventureShow and the FantasyShow classes implement the IShow interface:

public class AdventureShow : IShow

However, our client doesn’t need to know about these products, so let’s decouple our client by creating an abstract factory interface:

public interface IThemeParkFactory

{

IRide CreateRide();

IShow CreateShow();

}

Next, we’ll create a couple of concrete factories to implement this interface. Let’s start with the AdventureThemeParkFactory class:

public class AdventureThemeParkFactory : IThemeParkFactory

{

public IRide CreateRide()

{

return new AdventureRide();

}

public IShow CreateShow()

{

return new AdventureShow();

}

}

After that, let’s create a FantasyThemeParkFactory class:

public class FantasyThemeParkFactory : IThemeParkFactory

{

public IRide CreateRide()

{

return new FantasyRide();

}

public IShow CreateShow()

{

return new FantasyShow();

}

}

Now that we have the factory classes, let’s see how the Abstract Factory pattern helps us create families of related objects by updating our client:

public class ThemeParkClientNew

{

private readonly IRide _ride;

private readonly IShow _show;

public ThemeParkClientNew(IThemeParkFactory factory)

{

_ride = factory.CreateRide();

_show = factory.CreateShow();

}

public void EnjoyThemePark()

{

_ride.Start();

_show.Begin();

}

}

Here, the ThemeParkClientNew class is decoupled from specific implementations of rides and shows. It relies on abstractions (IRide and IShow) rather than concrete classes.

Adding new sections to the theme park now simply requires introducing a new factory implementation (e.g. SciFiThemeParkFactory), without modifying the existing client logic. This ensures our application is open to extension without modification, thus satisfying the open/closed design principle.

Benefits of the Abstract Factory Pattern

The Abstract Factory pattern offers several crucial advantages in software design.

First, the Abstract Factory encapsulates the creation of related objects, allowing clients to use families of objects without knowing about or being tied to the specific implementations. This in turn promotes modular and reusable code.

In addition, we define a common interface for the creation of related objects. Thus, we ensure that the objects produced by a factory are compatible and work seamlessly together. This consistency simplifies maintenance.

Finally, this pattern adheres to the open/closed design principle. Thus, we can introduce new variants of products through the creation of new concrete factories, without modifying existing client code.

Drawbacks of the Abstract Factory Pattern

Despite its benefits, this pattern has certain drawbacks that we should consider.

Implementing the Abstract Factory pattern involves defining multiple interfaces and their concrete implementations. This can make the code complex and difficult to understand, especially for someone new to the codebase. The complexity keeps growing as the number of product variants grows.

Also, as we are adding layers of abstraction, it might introduce some runtime overhead. While minimal, this overhead might be something to consider in a performance-sensitive application.

Lastly, while it’s easy to add a new family of products using the Abstract Factory pattern, extending existing families can be comparatively challenging.

Best Practices of the Abstract Factory Pattern

The very premise of the Abstract Factory design pattern depends upon the “composition over inheritance” principle. It helps us integrate various factories with the client classes. This allows us to have flexible designs and helps us avoid deep inheritance hierarchies.

We need to ensure that our abstract factory and product interfaces are well-defined. As these interfaces are the base of our design, they should encapsulate the necessary methods to create the product objects. This also includes grouping related products into families and defining interfaces for each product in the family. This makes sure that the client can use products from different families interchangeably.

Dependency injection is a really helpful tool while implementing this design pattern. We should leverage dependency injection to pass factory instances into the client classes. This promotes loose coupling and makes it easier for us to swap out factory implementations.

As it’s easy to get caught up in overusing any design pattern, we need to keep looking at the requirements at hand. Sometimes, a simpler Factory or Builder pattern might be enough. By overusing the Abstract Factory pattern, it’s possible to end up with overly complex class hierarchies. Thus, we should ensure that the abstraction provided by the factories genuinely adds value to our code.

Conclusion

In this article, we learned about the Abstract Factory design pattern and how it’s useful in applications dealing with the creation of objects. Especially when dealing with complex creation logic, it helps us centralize and maintain the creation process. Finally, we considered its benefits, drawbacks, and best practices.