If you followed along with the HTTP series, you are ready now to embark on a journey of HTTP security. And a journey it will be, I promise 🙂

Many companies have been a victim of security breaches. To name just a few prominent ones: Dropbox, Linkedin, MySpace, Adobe, Sony, Forbes, and many others were on the receiving end of malicious attacks. Many accounts were compromised and the chances are, at least one of those was yours 🙂

You can actually check that on Have I Been Pwned.

My email address was found on 4 different websites that were victims of a security breach.

There are many aspects of Web application security, too much to cover in one article, but let’s start right from the beginning. Let’s learn how to secure our HTTP communication first.

This is the fifth part of the HTTP Series.

In this article, you will learn more about:

There is a lot to cover, so let’s go right into it.

Do You Really Need HTTPS?

You might be thinking: “Surely not all websites need to be protected and secured”. If a website doesn’t serve sensitive data or doesn’t have any form submissions, it would be overkill to buy certificates and slow the website down, just to get the little green mark at the URL bar that says “Secured”.

If you own a website, you know it is crucial that it loads as fast as possible, so you try not to burden it with unnecessary stuff.

Why would you willingly go through the painful process of migration to the HTTPS just to secure the website that doesn’t need to be protected in the first place? And on top of that, you even need to pay for that privilege.

Let’s see if it’s worth the trouble.

HTTPS Encrypts Your Messages and Solves the MITM Problem

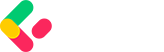

In the previous part of the HTTP series, we’ve talked about different HTTP authentication mechanisms and their security flaws. The problem that both Basic and Digest authentication cannot solve is the Man in the middle attack. Man in the middle represents any malicious party that inserts itself between you and the website you are communicating with. Its goal is to intercept the original messages both ways and hide their presence by forwarding the modified messages.

Original participants of the communication might not be aware that their messages are being listened to.

HTTPS solves the MITM attacks problem by encrypting the communication. Now, that doesn’t mean that your traffic cannot be listened to anymore. It does mean that anyone that listens and intercepts your messages, won’t be able to see its content. To decrypt the message you need the key. We will learn how that works exactly a bit later on.

Let’s move on.

HTTPS as a Ranking Signal

Not that recently, Google made HTTPS a ranking signal.

What does that mean?

It means that if you are a webmaster, and you care about your Google ranking, you should definitely implement the HTTPS on your website. Although it’s not as potent as some others signals like quality content and backlinks, it definitely counts.

By doing this, Google gives incentives to webmasters to move to HTTPS as soon as possible and improve the overall security of the internet.

It’s Completely Free

To enable HTTPS (SSL/TLS) for a website you need a certificate issued by a Certificate Authority. Until recently, certificates were costly and had to be renewed every year.

Thanks to the folks at Let’s encrypt you can get very affordable certificates now ($0!). Seriously, they are completely free.

Let’s Encrypt certificates that are easily installed, have major companies support, and a great community of people. Take a look at the Major sponsors and see for yourself the list of companies that support them. You might recognize a few 🙂

Let’s encrypt issues DV (domain validation) certificates only and have no plan of issuing organizational (OV) or extended validation (EV) certificates. The certificate lasts for 90 days and is easily renewed.

Like any other great technology, it has a downside too. Since certificates are easily available now, they are being abused by Phishing websites.

It’s All About the Speed

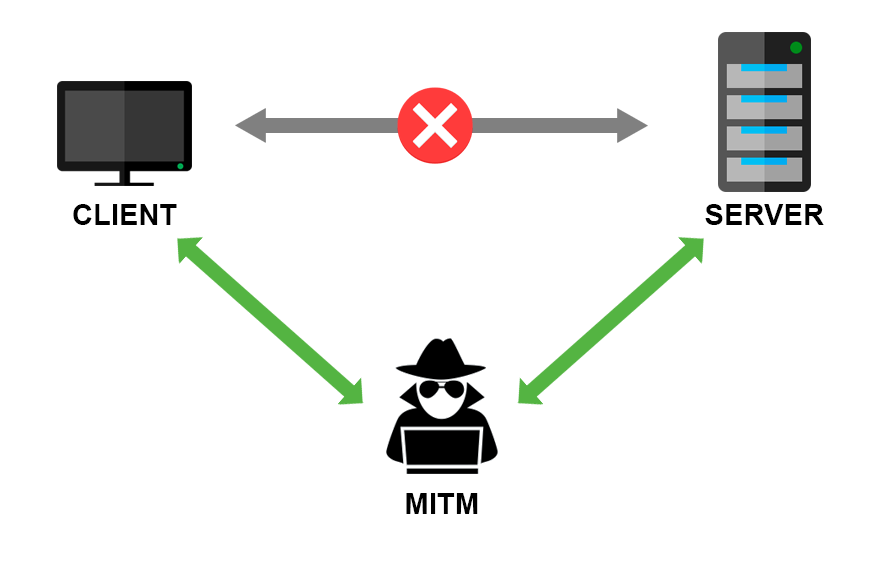

Many people associate HTTPS with additional speed overhead. Take a quick look at the httpvshttps.com.

Here are my results for the HTTP and HTTPS:

So what happened there? Why is HTTPS so much faster? How is that possible?

HTTPS is the requirement for using the HTTP 2.0 protocol.

If we look at the network tab, we will see that in the HTTPS case, the images were loaded over h2 protocol. And the waterfall looks very different too.

The HTTP 2.0 is the successor of the currently prevalent HTTP/1.1.

It has many advantages over HTTP/1.1:

- It’s binary, instead of textual

- It’s fully multiplexed, which means it can send multiple requests in parallel over a single TCP connection

- Reduces overhead by using HPACK compression

- It uses the new ALPN extension which allows for faster-encrypted connections

- It reduces additional round trip times (RTT), making your website load faster

- Many others

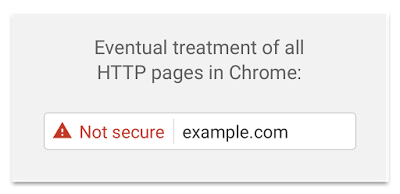

You Will Be Frowned Upon by Browsers

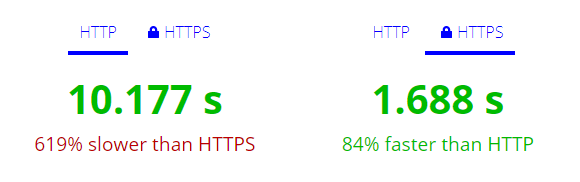

If you are not convinced by now, you should probably know, that some browsers started waging war against unencrypted content.

Here is how it looked before and after Chrome version 56.

And here is how it will look eventually.

Are you convinced yet? 😀

Moving to HTTPS Is Complicated

This is also the relic of past times. While moving to HTTPS might be harder for the websites that exist for a long time because of the sheer amount of resources uploaded to over HTTP, the hosting providers are generally trying to make this process easier.

Many hosting providers offer automatic migration to HTTPS. It can be as easy as clicking one button in the options panel.

If you plan to set up your website over HTTPS, check if the hosting provider offers HTTPS migration first. Or if it has shell access, so you can do it yourself easily with let’s encrypt and a bit of server configuration.

So, these are the reasons to move to HTTPS. Any reason not to?

Hopefully, by now, I convinced you of the HTTPS value and you passionately want to move your website to HTTPS and understand how it works.

HTTPS Fundamental Concepts

HTTPS stands for Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure. This effectively means that the client and server communicate through HTTP but over the secure SSL/TLS connection.

In the previous parts of the series, we’ve learned how HTTP communication works, but what does the SSL/TLS part stand for and why do I use both SSL and TLS?

Let’s start with that.

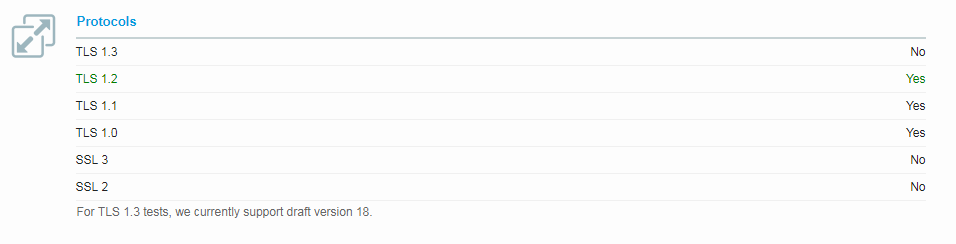

SSL vs TLS

Terms SSL (Secure Socket Layer) and TLS (Transport Layer Security) are used interchangeably, but in fact, today, when someone mentions SSL they probably mean TLS.

SSL was originally developed by Netscape but version 1.0 never saw the light of the day. Version 2.0 was introduced in 1995 and version 3.0 in 1996, and they were used for a long time after that (at least what is considered long in IT), even though their successor TLS already started taking traction. Up until 2014. fallback from TLS to SSL was supported by servers, and that was the main reason the POODLE attack was so successful.

After that, the fallback to SSL was completely disabled.

If you check yours or any other website with Qualys SSL Labs tool, you will probably see something like this:

As you can see, SSL 2 and 3 are not supported at all, and TLS 1.3 hasn’t still taken off.

But, because SSL was so prevalent for so long, it became a term that most people are familiar with and now it’s used for pretty much anything. So when you hear someone using SSL instead of TLS it is just for historical reasons, not because they really mean SSL.

Now that we got that out of the way, I will use TLS from now on since it’s more appropriate.

So, how do the client and the server establish a secure connection?

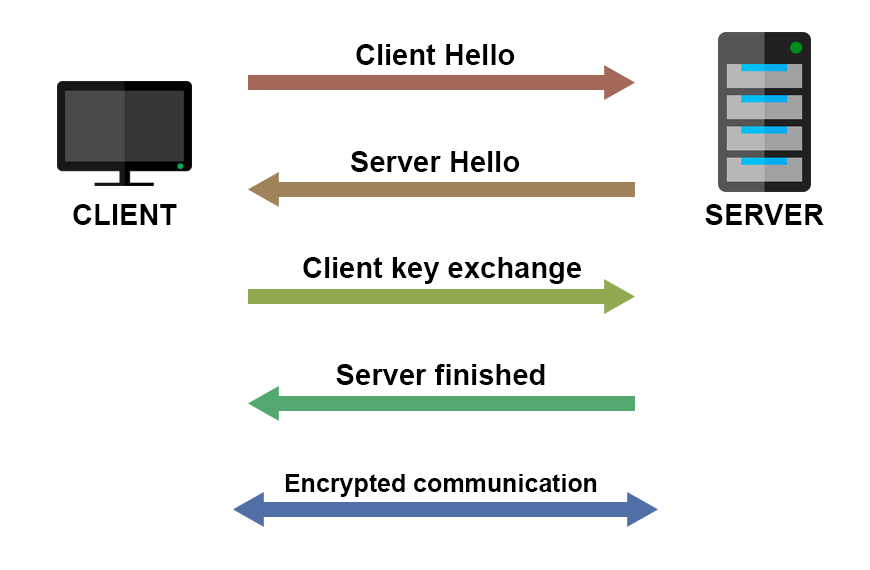

TLS Handshake

Before the real, encrypted communication between the client and server starts, they perform what is called the “TLS handshake”.

Here is how TLS handshake works (very simplified, additional links below).

The encrypted communication starts after the connection is established.

The actual mechanism is much complicated than this, but to implement the HTTPS, you don’t need to know all the actual details of the TLS handshake implementation.

What you need to know is that there is an initial handshake between the client and the server, in which they exchange keys and certificates. After that handshake, encrypted communication is ready to start.

If you want to know exactly how TLS Handshake works, you can look it up in the RFC 2246.

In the TLS handshake image, certificates are being sent, so let’s see what a certificate represents and how it’s being issued.

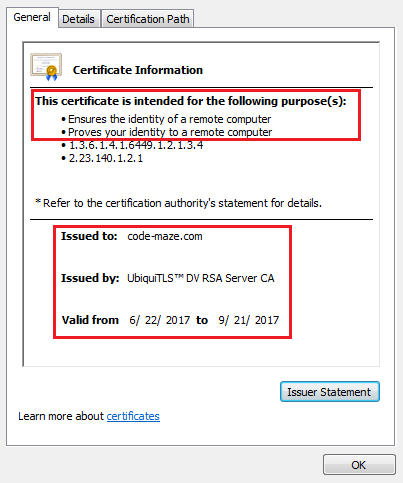

Certificate and Certification Authorities (CAs)

Certificates are the crucial part of the secure communication over HTTPS. They are issued by one of the trusted Certification Authorities.

A digital certificate allows the users of the website to communicate in the secure fashion when using a website.

For example, the certificate you are using when browsing through my blog looks like this:

If you are using Chrome, for example, you can inspect certificates yourself by going to the Security tab in Developer Tools (F12).

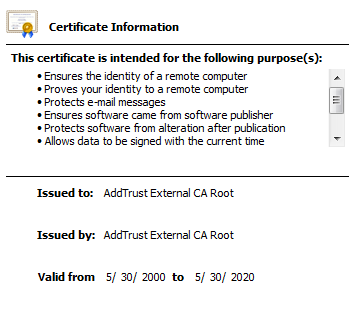

I would like to point out two things. In the first red box, you can see what the real purpose of the certificate is. It just ensures that you are talking to the right website. If someone was to for example impersonate the website you think you are communicating with, you would certainly get notified by your browser.

That would not prevent malicious attackers to steal your credentials if they have a legitimate domain with a legitimate certificate. So be careful. Green “Secure” in the top left just means that you are communicating with the right website. It doesn’t say anything about the honesty of that website’s owner 🙂

Extended validation certificates, on the other hand, prove that the legal entity is controlling the website. There is an ongoing debate whether EV certs are all that useful to the typical user of the internet. You can recognize them by the custom text left of your URL bar. For example, when you browse twitter.com you can see:

![]()

That means they are using EV certificate to prove that their company stands behind that website.

Certificate Chains

So why would your browser trust the certificate that server sends back? Any server can send a piece of digital documentation and claim it is what you want it to be.

That’s where root certificates come in. Typically certificates are chained and the root certificate is one your machine implicitly trusts.

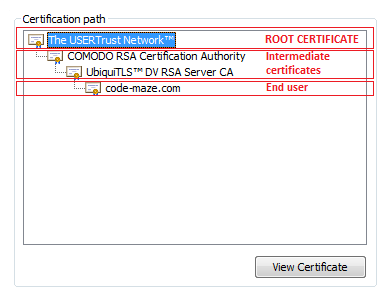

For my blog it looks like this:

Lowest one is my domain certificate, which is signed by the certificate above it and so on… Until the root certificate is reached.

But who signs the root certificate you might wonder?

Well, it signs itself 😀

Issued to: AddTrust External CA Root, Issued by: AddTrust External CA Root.

And your machine and your browsers have a list of trusted root certificates which they rely upon to ensure the domain you are browsing is trusted. If the certificate chain is broken for some reason (happened to me because I enabled CDN for my blog), your site will be displayed as insecure on some machines.

You can check the list of trusted root certificates on Windows by running the certificate manager by pressing the windows button + R and typing certmgr.msc. You can then find machine trusted certificates in the Trusted Root Certification Authorities section. This list is used by Windows, IE, and Chrome. Firefox, on the other hand, manages its own list.

By exchanging certificate, client and server know that they are talking to the right party and can begin encrypted message transfer.

HTTPS Weaknesses

HTTPS can provide a false sense of security if the site backend is not properly implemented. There are a plethora of different ways to extract customer information, and many sites are leaking data even if they are using HTTPS. There are many other mechanisms besides MITM to get sensitive information from the website.

Another potential problem that the websites can have HTTP links even though they run over HTTPS. This can be a chance for a MITM attack. While migrating websites to HTTPS, this might get by unnoticed.

And here is another one as a bonus: login forms accessed through an insecure page could potentially be at risk even though they are loaded on a secure page. So it’s best to keep the entire website secure to avoid this one.

Conclusion

That wraps up the entire HTTP series. We hope you got something useful out of it and understood some concepts you didn’t or couldn’t before.

We know we had fun writing it and learned a bunch of new things in the process. Hopefully, it was as much fun reading (or at least close). 🙂