In the first article of the series, we talked about the basic concepts of the HTTP. Now that we have some foundation to build upon, we can talk about some of the architectural aspects of the HTTP. There is more to HTTP than just sending and receiving data.

HTTP cannot function by itself as an application protocol. It needs infrastructure in the form of hardware and software solutions that provide different services and make the communication over the World Wide Web possible and efficient.

This is the second part of the HTTP Series.

In this article, you will learn more about:

These are an integral part of our internet life, and you will learn exactly what the purpose of each one of these is, and how it works. This knowledge will help you connect the dots from the first article, and understand the flow of the HTTP communication even better.

So let’s start.

Web Servers

As the first article explained, the primary function of a Web server is to store the resources and to serve them upon receiving requests. You access the Web server using a Web client (aka Web browser) and in return get the requested resource or change the state of existing ones. Web servers can be accessed automatically too, using Web crawlers, that we will talk about later in the article.

Some of the most popular Web servers out there and probably the ones you heard of are Apache HTTP Server, Nginx, IIS, Glassfish…

Web servers can vary from the very simple and easy to use, to sophisticated and complicated pieces of software. Modern Web servers are capable of performing a lot of different tasks. Basic tasks that Web server should be able to do:

- Set up connection – accept or close the client connection

- Receive request – read an HTTP request message

- Process request – interpret the request message and take action

- Access resource – access the resource specified in the message

- Construct response – create the HTTP response message

- Send response – send the response back to the client

- Log transaction – write about the completed transaction in a log file

I will break up the basic flow of the Web server in a few different Phases. These phases represent a very simplified version of the Web server flow.

Phase 1: Setting up a connection

When Web client wants to access the Web server, it must try to open a new TCP connection. On the other side, the server tries to extract the IP address of the client. After that, it is up to the server to decide to open or close the TCP connection to that client.

If the server accepts the connection, it adds it to the list of existing connections and watches the data on that connection.

It can also close the connection if the client is not authorized or blacklisted (malicious).

The server can also try to identify the hostname of the client by using the “reverse DNS”. This information can help when logging the messages, but hostname lookups can take a while, slowing the transactions.

Phase 2: Receiving/Processing requests

When parsing the incoming requests, Web servers parse the information from the message request line, headers, and body (if provided). One thing to note is that the connection can pause at any time, and in that case, the server must store the information temporarily until it receives the rest of the data.

High-end Web servers should be able to open many simultaneous connections. This includes multiple simultaneous connections from the same client. A typical web page can request many different resources from the server.

Phase 3: Accessing the resource

Since Web servers are primarily the resource providers, they have multiple ways to map and access the resources.

The simplest way is to map the resource is to use the request URI to find the file in the Web server’s filesystem. Typically, the web server puts them in a special folder, called docroot. For example, docroot on the Windows server can be located on F:\WebResources\. If a GET request wants to access the file on the /images/codemazeblog.txt, the server translates this to F:\WebResources\images\codemazeblog.txt and returns that file in the response message. When more than one website is hosted on a Web server, each one can have its separate docroot.

If a Web server receives a request for a directory instead of a file, it can resolve it in a few ways. It can return an error message, return the default index file instead of the directory or scan the directory and return the HTML file with contents.

The server may also map the request URI to the dynamic resource – a software application that generates some results. There is a whole class of servers called application servers which purpose is to connect web servers to the complicated software solutions and serve dynamic content.

Phase 3: Generating and sending the response

Once the server identified the resource it needs to serve, it forms the response message. The response message contains the status code, response headers, and response body if one was needed.

If the body is present in the response, the message usually contains the Content-Length header describing the size of the body and the Content-Type header describing the MIME type of the returned resource.

After generating the response, the server chooses the client it needs to send the response to. For the nonpersistent connections, the server needs to close the connection when the entire response message is sent.

Phase 4: Logging

When the transaction is complete, the server logs all the transaction information in the file. Many servers provide logging customizations.

Proxy Servers

Proxy servers (proxies) are the intermediary servers. They are often found between the Web server and Web client. Due to their nature, proxy servers need to behave both like a Web client and a Web server.

But why do we need Proxy servers? Why don’t we just communicate directly between Web clients and Web servers? Isn’t that much simpler and faster?

Well, simple it may be, but faster, not really. But we will come to that.

Before explaining what proxy servers are, we need to get one thing out of the way. That is the concept of reverse proxy or the difference between the forward proxy and reverse proxy.

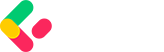

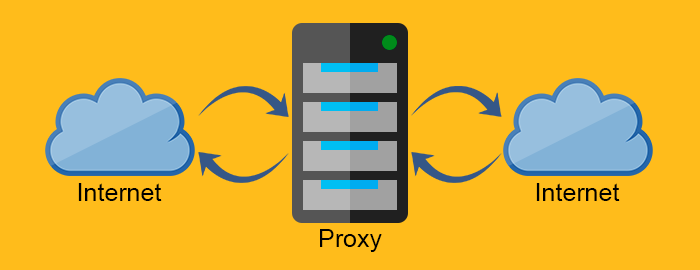

The forward proxy acts as a proxy for the client requesting the resource from a Web server. It protects the client by filtering requests through the firewall or hiding the information about the client. The reverse proxy, on the other hand, works exactly the opposite way. It is usually placed behind the firewall and protects the Web servers. For all the clients know, they talk to the real Web server and remain unaware of the network behind the reverse proxy.

Proxy server

Reverse proxy server

Proxies are very useful and their application is pretty wide. Let’s go through some of the ways you can use proxy servers.

- Compression – Compressing the content directly increases the communication speed. Simple as that.

- Monitoring and filtering – Want to deny access to adult websites to the children in the elementary school? The proxy is the right solution for you 🙂

- Security – Proxies can serve as a single entry point to the entire network. They can detect malicious applications and restrict application-level protocols.

- Anonymity – Requests can be modified by the proxy to achieve greater anonymity. It can strip the sensitive information from the request and leave just the important stuff. Although sending less information to the server might degrade the user experience, anonymity is sometimes the more important factor.

- Access control – Pretty straightforward, you can centralize the access control of the many servers on a single proxy server.

- Caching – You can use the proxy server to cache the popular content, and thus greatly reduce the loading speeds.

- Load balancing – If you have a service that gets a lot of “peak traffic” you can use a proxy to distribute the workload on more computing resources or Web servers. Load balancers route traffic to avoid overloading the single server when the peak happens.

- Transcoding – Changing the contents of the message body can also be the proxy’s responsibility

As you can see, proxies can be very versatile and flexible.

Caching

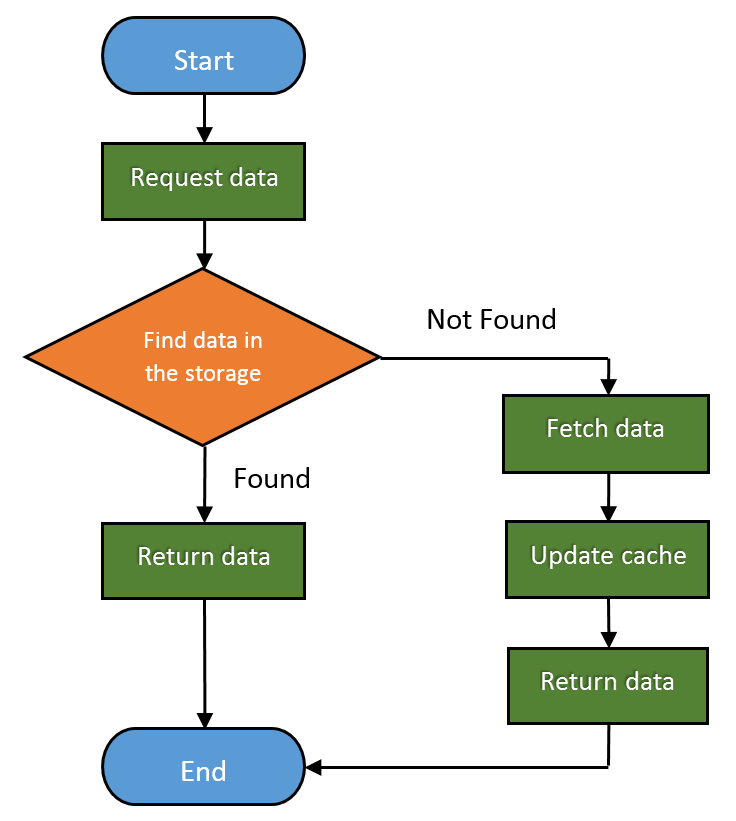

Web caches are devices that automatically make copies of the requested data and save them in the local storage.

By doing this, they can:

- Reduce traffic flow

- Eliminate network bottlenecks

- Prevent server overload

- Reduce the response delay on long distances

So you can clearly say that Web caches improve both user experience and Web server performance. And of course, potentially save a lot of money.

The fraction of the requests served from the cache is called Hit Rate. It can range from 0 to 1, where 0 is 0% and 1 is 100% request served. The ideal goal is of course to achieve 100%, but the real number is usually closer to 40%.

Here is how the basic Web cache workflow looks like:

Gateways, Tunnels, and Relays

In time, as the HTTP matured, people found many different ways to use it. HTTP became useful as a framework to connect different applications and protocols.

Let’s see how.

Gateways

Gateways refer to pieces of hardware that can enable HTTP to communicate with different protocols and applications by abstracting a way to get a resource. They are also called the protocol converters and are far more complex than routers or switches due to the usage of multiple protocols.

You can, for example, use a gateway to get the file over FTP by sending an HTTP request. Or you can receive an encrypted message over SSL and convert it to HTTP (Client-Side Security Accelerator Gateways) or convert HTTP to a more secure HTTPS message (Server-Side Security Gateways).

Tunnels

Tunnels make use of the CONNECT request method. They enable sending non-HTTP data over HTTP. The CONNECT method asks the tunnel to open a connection to the destination server and to relay the data between the client and the server.

CONNECT request:

CONNECT api.github.com:443 HTTP/1.0 User-Agent: Chrome/58.0.3029.110 Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml

CONNECT response:

HTTP/1.0 200 Connection Established Proxy-agent: Netscape-Proxy/1.1

The CONNECT response doesn’t need to specify the Content-Type unlike a normal HTTP response would.

Once the connection establishes, we can send the data between the client and the server directly.

Relays

Relays are the outlaws of the HTTP world and they don’t need to abide by the HTTP laws. They are dumbed-down versions of proxies that relay any information they receive as long as they can establish a connection using the minimal information from the request messages.

The sole existence stems from the need to implement a proxy with as little trouble as possible. That can also potentially lead to trouble, but its use is very situational and there is certainly a risk to benefit ratio to consider when implementing relays.

Web Crawlers

Also, popularly called spiders, they are bots that crawl over the World Wide Web and index its contents. So, the Web crawler is an essential tool for Search engines and many other websites.

The web crawler is a fully automated piece of software and it doesn’t need human interaction to work. The complexity of web crawlers can vary greatly and some of the web crawlers are pretty sophisticated pieces of software (like the ones search engines use).

Web crawlers consume the resources of the website they are visiting. For this reason, public websites have a mechanism to tell the crawlers which parts of the website to crawl, or to tell them not to crawl anything at all. You can do this by using the robots.txt (robots exclusion standard).

Of course, since it is just a standard, robots.txt cannot prevent uninvited web crawlers to crawl the website. Some of the malicious robots include email harvesters, spambots, and malware.

Here are a few examples of the robots.txt files:

User-agent: * Disallow: /

This one tells all the crawlers to stay out.

User-agent: * Disallow: /somefolder/ Disallow: /notinterestingstuff/ Disallow: /directory/file.html

And this one refers only to these two specific directories and a single file.

User-agent: Googlebot Disallow: /private/

You can disallow a specific crawler, like in this case.

But given the vast nature of the World Wide Web, even the most powerful crawlers ever made cannot crawl and index the entirety of it. And that’s why they use selection policy to crawl the most relevant parts of it. Also, the WWW changes frequently and dynamically, so the crawlers must use the freshness policy to calculate whether to revisit websites or not. And since crawlers can easily overburden the servers by requesting too much too fast, there is a politeness policy in place. Most of the know crawlers use the intervals of 20 seconds to 3-4 minutes to poll the servers to avoid generating the load on the server.

You might have heard the news of the mysterious and evil deep web or dark web. But it’s nothing more than the part of the web, that is intentionally not indexed by search engines to hide the information.

Conclusion

This wraps it up for this part of the HTTP series. You should now have an even better picture of how the HTTP works, and that there is a lot more to it than requests, responses, and status codes. There is a whole infrastructure of different hardware and software pieces that HTTP utilizes to achieve its potential as an application protocol.

Every concept I talked about in this article is large enough to cover the whole article or even a book. Our goal was to roughly present you with the different concepts so that you know how it all fits together, and what to look for when needed.

If you found some of the explanations a bit short and unclear and you missed my previous articles, be sure to visit part 1 of the series and the HTTP reference where I talk about basic concepts of the HTTP.

Thank you for reading and stay tuned for part 3 of the series where I explain different ways servers can use to identify the clients.