In this article, we are going to talk about a popular design pattern, the Mediator Pattern. We will see how this pattern helps address some design problems and how to implement it in C#.

Let’s start.

What is The Mediator Design Pattern?

Mediator is a behavioral design pattern that promotes loose coupling by eliminating chaotic inter-dependencies.

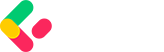

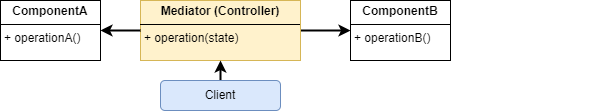

This pattern emphasizes the use of a mediator instead of direct interaction between components:

The Mediator sits at the center of this structure which can be orchestrated as a pair of IMediator interface and its concrete implementation. A mediator receives notifications from one component and decides which other component can carry out further operations and interact accordingly.

Components (aka colleagues) are unaware of other components, reflecting the key purpose of this pattern. A component may notify the Mediator with relevant event/state data during a certain operation. The event carries the necessary information to help the mediator choose the next component to interact with. A component may also receive a reaction from the mediator as an aftereffect of another component’s operation.

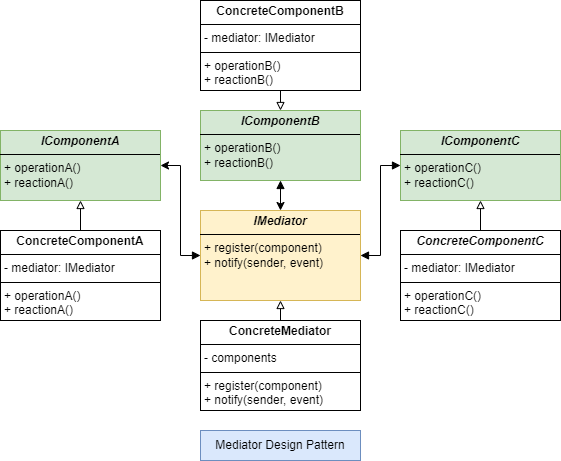

Before a mediator can act as a liaison, it needs a way to establish connections with the participating components:

One way to do this is to declare a property for each component and assign it explicitly from the client code (Figure 1). This is the case when components do not share a base class/interface. However, a more favorable approach is to provide a method to register components by their shared contract (Figure 2).

Intercommunication Between Components

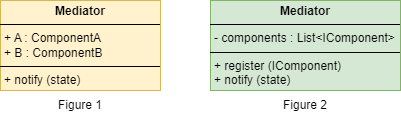

The true intent of a mediator is to coordinate intercommunication between components. Hence a classic mediator facilitates bi-directional interaction:

As we see, the execution flow starts from the component end, like when the client code invokes operationA() on ComponentA, for example. During the execution of operationA(), the Mediator receives feedback and executes reactionB() on ComponentB. A similar execution flow happens when the client invokes the operation on ComponentB.

So, in a bi-directional flow, components are subjected to a level of coupling to the mediator.

Sometimes it’s more favorable when components are completely unaware of the mediator. This is possible when we design the mediator as a controller rather than a coordinator.

Such cases involve one-way communication between the mediator and components:

This approach eliminates the need for mediator-coupling inside the components and offers more centralized control. However, it comes with the price of less modularity which may not be favorable in many situations. Also, it deviates from the traditional intent of the mediator and may closely resemble the observer pattern.

In this article, we will follow the classic approach of a mediator.

What Problem Does The Mediator Pattern Solve?

To better understand how the Mediator pattern works, let’s first talk about the problem it can resolve.

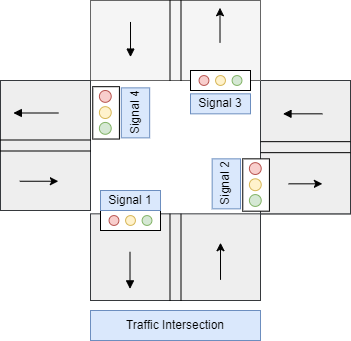

Let’s imagine a traffic intersection that involves 4 signal points:

Signal1 and Signal3 control the traffic moving along north-south. Similarly, Signal2 and Signal4 control the traffic along east-west.

For the sake of simplicity, we consider only the basic traffic rule – before allowing traffic to move in a particular direction, the traffic moving across that direction must be stopped.

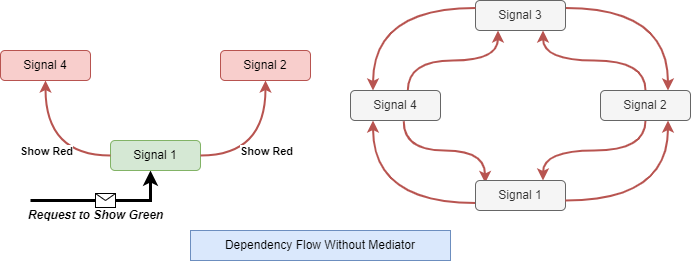

Let’s visualize the provision of this rule when Signal1 receives a request for the green signal:

Before showing the green light on Signal1, we have to show the red light on Signal2 and Signal4. The same principle applies to all four signal points. As a result, we observe a web of inter-dependencies! Every signal point needs access to other signals leading to a chaotic dependency flow.

The chaos becomes more apparent when we try to implement the signal components based on direct relationships.

The Signal1:

public class Signal1() : SignalBase(SignalName.Signal1)

{

public void ShowGreenLight(Signal2 signal2, Signal4 signal4)

{

signal2.ShowRedLight();

signal4.ShowRedLight();

ChangeLight(TrafficLight.Green);

}

public void ShowRedLight() => ChangeLight(TrafficLight.Red);

}

The Signal2:

public class Signal2() : SignalBase(SignalName.Signal2)

{

public void ShowGreenLight(Signal1 signal1, Signal3 signal3)

{

signal1.ShowRedLight();

signal3.ShowRedLight();

ChangeLight(TrafficLight.Green);

}

public void ShowRedLight() => ChangeLight(TrafficLight.Red);

}

To serve the ShowGreenLight() request for Signal1, we need access to instances of Signal2, and Signal4. Similarly, Signal2 implementation depends on Signal1 and Signal3. Because of circular relationships, we can not provide these dependencies as part of the constructor parameters. So we have to supply them as arguments of ShowGreenLight() method.

Alternatively, we could explicitly expose the dependent signals as properties and assign them from the client code before invoking ShowGreenLight().

Either way, we end up with a tightly coupled workflow. Any change in the dependency line of any signal component needs to reflect on others as well. Such a design suffers from poor maintainability, less adaptability, and a higher risk of bugs.

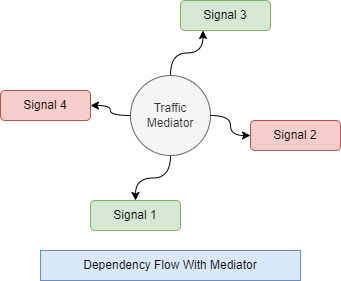

The mediator pattern effectively addresses this problem by offering a central point of all inter-communications:

By using a TrafficMediator, we can centralize the logic of signal interactions and break the web of dependencies!

Implementation of Mediator Pattern in C#

So, let’s refactor our traffic-control system using the mediator pattern.

To begin, we need a contract for the mediator:

public interface ITrafficMediator

{

void RequestClearance(SignalName signalName);

}

The ITrafficMediator interface defines a method that will hold the interaction logic when a signal requests clearance.

Since all our signal components exhibit the same behavior, we can place the core in a base class:

public abstract class SignalBase(ITrafficMediator mediator, SignalName name)

{

public SignalName Name => name;

public TrafficLight Light { get; private set; }

public void ShowGreenLight()

{

mediator.RequestClearance(Name);

ChangeLight(TrafficLight.Green);

}

// omitted for brevity

}

The default constructor lets us initialize the necessary properties. Additionally, this time we also pass the mediator as a constructor dependency.

Talking about the refactored ShowGreenLight() implementation – instead of calling other signal components, we request the mediator for signal clearance. All inter-communication logic will go inside the mediator.

The concrete signal classes are now just one-liner codes varied by their Name only.

The Signal1:

public class Signal1(ITrafficMediator mediator) : SignalBase(mediator, SignalName.Signal1) { }

The Signal2:

public class Signal2(ITrafficMediator mediator) : SignalBase(mediator, SignalName.Signal2) { }

And so on.

Finally, it’s time to implement the concrete mediator:

public class TrafficMediator : ITrafficMediator

{

private Signal1? _signal1;

private Signal2? _signal2;

private Signal3? _signal3;

private Signal4? _signal4;

public void Register(Signal1 signal1, Signal2 signal2, Signal3 signal3, Signal4 signal4)

{

_signal1 = signal1;

_signal2 = signal2;

_signal3 = signal3;

_signal4 = signal4;

}

public void RequestClearance(SignalName signalName)

{

switch (signalName)

{

case SignalName.Signal1:

case SignalName.Signal3:

_signal2?.ShowRedLight();

_signal4?.ShowRedLight();

break;

case SignalName.Signal2:

case SignalName.Signal4:

_signal1?.ShowRedLight();

_signal3?.ShowRedLight();

break;

default:

throw new InvalidOperationException($"Unrecognized signal - {signalName}");

}

}

}

By using Register() method, we can establish the connection to the participating signals. And the most interesting bit, the core communication logic, goes inside the RequestClearance() method.

Inside the RequestClearance() method, we can decide which signals need to be turned off based on the requesting SignalName. Anytime we need a change in interaction logic such as introducing new signal points, we can do that by revising RequestClearance() method!

This is how a mediator can help us control a system of interlaced dependencies.

Verify the Execution Flow

Our traffic-control system is ready.

Let’s set up the mediator and request the green light on Signal1:

var mediator = new TrafficMediator(); var signal1 = new Signal1(mediator); var signal2 = new Signal2(mediator); var signal3 = new Signal3(mediator); var signal4 = new Signal4(mediator); mediator.Register(signal1, signal2, signal3, signal4); signal1.ShowGreenLight();

As we inspect the execution flow:

Signal2 is Red Signal4 is Red Signal1 is Green

We see all related signals are notified and reflect the desired traffic light.

Drawbacks of Mediator Pattern

Although the mediator contributes to loose coupling and centralized communication control, it has some drawbacks too.

Introducing a mediator means introducing an additional layer of indirection. This also means extra complexity, maintenance overhead, and difficulty in testing.

Indirect interaction is usually subjected to additional conditions and is likely to be slower than direct interaction. So the performance overhead can be a potential concern for a complex mediator.

Because of centralized communication logic, the mediator may turn to a big monolithic class when many interacting events are involved. Such cases are difficult to maintain and prone to side effects.

In short, the mediator pattern is not a silver bullet. It can bring more problems than it solves if not carefully designed.

Conclusion

In this article, we learned how to use the Mediator design pattern in a C# application and how this pattern can reduce the web of dependencies. We have also discussed some factors we should consider while using such patterns.